Unless we’ve given up television for Lent — or for life — we’ve all seen the opioid ads and have heard the plaintive cries, “Give me my Aleve.” There are two certain things about pain: 1) We don’t like it; 2) We want to get rid of it as quickly as possible, preferably by popping a pill.

As we wind toward the end of the season of what our Orthodox brothers and sisters call Great Lent, we might find it useful to think about our attitudes toward pain.

The old “No pain, no gain” is instructive. It reminds us that worthwhile goals and holy projects can cost us something. As St. Paul says, “Every athlete exercises discipline … They do it to win a perishable crown, but we an imperishable one. … [So] I drive my body and train it” (1 Cor 9:25, 27). Our Lenten fast, abstinence, and list of things given up are forms of self-denial which incline us toward positive self-control. Hunger pangs, voluntary deprivation, and delayed gratification do us some good. We lose weight, learn to bypass our cravings, and practice the fine art of waiting.

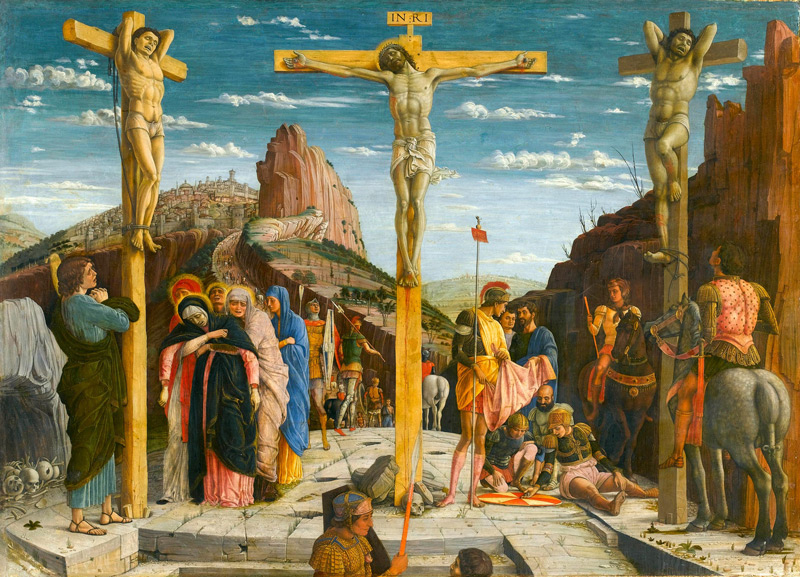

Beyond that, we attune ourselves more closely to the sacrifices and sufferings of Christ. Our Lenten penances do the most good when we offer our self-discipline for some greater cause. The money we save can go to the poor, as can the clothes that are now too large. The pinch of poverty or lack can help grow our empathy for the world’s hungry and homeless. We realize that our list of must-haves is frivolous. We grow in virtue by practicing it.

Aside from all the ways in which Lenten practices can bolster our spiritual growth, there are some other interesting points to be considered when we think of the topic of pain. While we know that God desires our health and flourishing, we can also see that pain can be a powerful impetus.

There are a number of medical and psychological studies that show that pain can spark large-scale humanitarian projects and artistic creativity.

We think of Florence Nightingale, who was ill and homebound for just a little less than two-thirds of her long life. Elizabeth Barrett Browning and a long list of coughing British poets who preceded her (and died young) have blessed us with classic literary works. Abraham Lincoln may have had Marfan syndrome. Helen Keller, deaf and blind, became a lecturer and political activist. Violinist Itzhak Perlman used to clamber onto the concert stage with crutches, the result of childhood polio. Now he uses an electric scooter and sits to play exquisite violin. A theory developed in the 1980s and 1990s is that concentrated activity has a narcotic effect. Thus, people who focus on inventing, creating, and serving may find absorbing pursuits to be the best pain relief available.

It’s all about self-forgetfulness. And that, of course, is the invitation of Lent and Holy Week.