Perhaps Bishop John England used a strategy which many of us in the pro-life movement must employ. When it seems impossible to eradicate a wrong totally, one takes steps to mitigate its effects. If we can’t get a human life amendment, we demonstrate and promote smaller legislative actions. The idea is to do something, even if one cannot do everything.

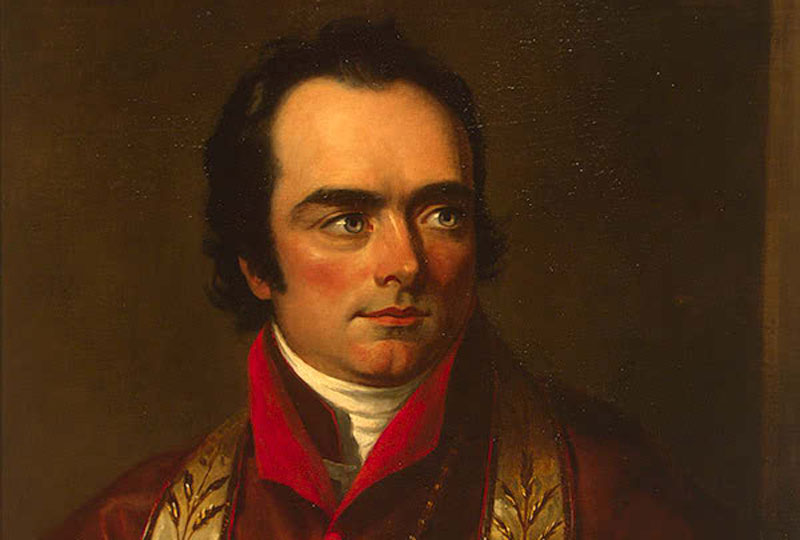

John England found himself in a quandary as the bishop of the new Diocese of Charleston in 1820. Slave holding and the retention of indentured servants was commonplace in the still-new nation. His diocese covered the Carolinas and Georgia — with a collective population of Catholics comparable to today’s head count at St. Gregory the Great in Bluffton, or St. Mary Magdalene in Simpsonville. These Catholics lived on or were amidst working plantations, and those plantations had slaves.

There were few Catholics who knew that popes in 1435 and 1537 (Eugene IV and Paul III) had stridently condemned the slave trade and the treatment of native peoples from Africa and the new-found Americas like livestock. These papal condemnations were issued in Latin in a time of slow communications and so had limited currency. That’s been an age-old problem. Even now, with a Vatican website (www.vatican.va) available in nine languages, we rarely find people who actually read papal statements in their entirety.

Historians note that Bishop England brought with him from Ireland an abiding compassion for the oppressed, and he did know papal teachings. His family had suffered anti-Catholic prejudice and enforced poverty. Among his early acts as bishop was to celebrate Mass and vespers each Sunday for Africans. In 1830, he established the Sisters of Charity of Our Lady of Mercy, who had a founding commitment to educate needy girls, including free Africans, and give religious instruction to female slaves. In 1831 and 1835, he opened schools for girls and boys of African descent. These suffered temporary closure as anti-abolitionist sentiment heated up, but he reopened at least one of these schools by 1841.

Despite these efforts, Bishop England is sometimes faulted for compromising on slavery. On one hand, he is hailed for public actions on behalf of free Africans. On the other, he is criticized for finessing the stance of Pope Gregory XVI. In 1839 news came from abroad that this pope had reiterated the Church’s condemnations of the slave trade.

Bishop England interpreted this to mean that it was immoral for Catholics to seize people from their homelands and market them as commodities. He did not, however, read the pope as opposing existing domestic slavery. England indicated that slave-holding was a part of human history and that Scripture acknowledged the existence of slavery.

He didn’t strongly emphasize the Church’s regard for slaves as fully human persons and didn’t highlight St. Paul’s admonition to Philemon to receive the slave Onesimus “no longer as a slave but more than a slave, a brother.”

Perhaps John England was living another of Paul’s admonitions — one addressed to Corinthians: “I fed you milk, not solid food, because you were unable to take it.” Are we, who know of rampant abortion, human trafficking, and resurgent racism there yet? Can we take truth?

Sister Pamela Smith, SSCM, is the Secretary for Education and Faith Formation at the Diocese of Charleston. Email her at psmith@catholic-doc.org.