GREENVILLE—A year ago, Jennie Neighbors took a group of students from St. Joseph’s Catholic School to Alabama, where they learned about some of the history of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ’60s, with stops at landmarks in Birmingham, Selma and Montgomery.

While in Montgomery, they heard a talk from Anthony Ray Hinton, who spent nearly 30 years in an Alabama prison for crimes he did not commit.

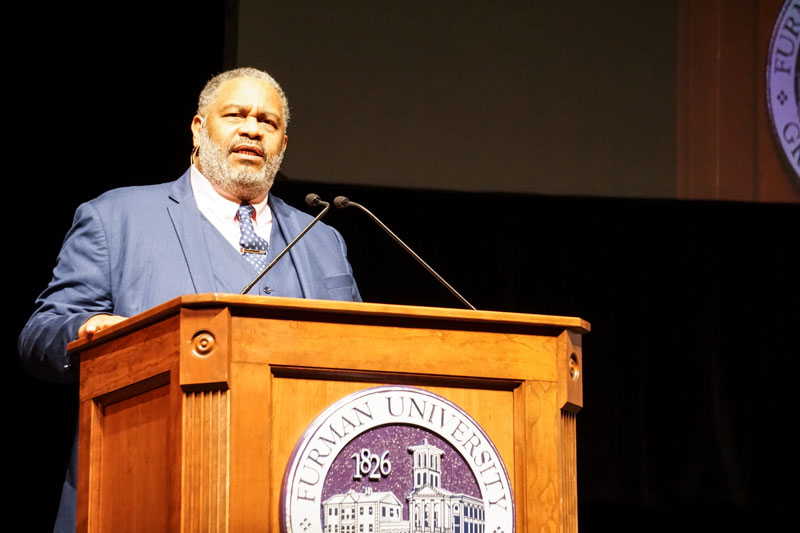

Recently, Neighbors and many of those same students went to Furman University to hear Hinton’s story of how he was falsely accused and convicted in 1985 of committing two murders near Birmingham, and how his faith in God helped him through his time on Death Row and ultimately to freedom in 2015.

Hinton made an impact on the group during their tour last year, which included a stop at the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, where Hinton works as community educator. Neighbors, who teaches English at St. Joseph’s and is director of the school’s Pope Francis Forum for Dialogue and Diversity, helped bring Hinton to Greenville. St. Joseph’s sponsored the event along with Furman University’s NAACP, religious council, poverty awareness committee, and its student diversity council.

As part of his work at the initiative, Hinton shares his story at churches and college campuses across the country. In March 2018, he published a memoir titled “The Sun Does Shine: How I Found Life and Freedom on Death Row.”

Hinton was arrested in the summer of 1985 following the robbery and shooting deaths of two Birmingham area fast-food restaurant managers. A jury found him guilty of the crimes and he was sent to Holman Correctional Facility in southern Alabama to await execution.

Attorneys with the Equal Justice Initiative, which describes itself as a private, nonprofit organization that “challenges poverty and racial injustice (and) advocates for equal treatment in the criminal justice system,” began litigating on behalf of Hinton in 2002, focusing their arguments, in part, on evidence presented in the initial trial related to the weapon used in the shootings.

Following a denial by the state of Alabama to reopen the case, plus another dozen years of litigation by the institute in behalf of Hinton, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the lower court’s decision in 2014 and a new trial was granted. According to the institute, a judge dismissed the charges after subsequent state forensic scientists’ tests found the bullets recovered at the crime scenes did not match the weapon prosecutors said Hinton used to kill the two restaurant managers in 1985.

Hinton was released from prison in April of 2015.

Hinton told the audience at Furman that he was “full of hatred” while being held in solitary confinement his first three years at Holman. By his fourth year in prison, Hinton realized that in order to survive he needed to change his outlook — rid himself of his hatred and turn back to God. Hinton turned his anger into hope, not only for himself but also his fellow inmates on Death Row, some of whom were executed not far from his own cell.

“My mother taught me compassion,” Hinton said, a lesson he drew from repeatedly while at Holman, including befriending the son of a grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan on Death Row. “We showed him what true love was.”

Ultimately, it was forensic science that freed Hinton from prison, a revelation that brought both a smile and a tear to the face of Joanna McLucas, a forensics sciences teacher at St. Joseph’s.

A parishioner at St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Church in Simpsonville, McLucas said she brought her students to hear Hinton’s story and make the connection between what they’re learning in the classroom with positive, real-world outcomes that arise from forensics science.

“As a teacher I wanted my students to experience this and to hear (Hinton) speak,” McLucas said.

Though he admits he “lost God” for a time while at Holman, and that it took a while to get God back in his life, Hinton said his faith is what ultimately got him through it.

Hinton said amid the horror of a life in prison he learned to escape through humorous mind games and reading.

“When you face tragedy, you have to find laughter,” he said, an avenue he found through his faith. “God doesn’t put you in anything you can’t get yourself out of, if you put your faith in him.”