It seems that the Holy Spirit is the most neglected member of the Blessed Trinity. So it should not surprise us that the third of the big three liturgical events of the year — Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost — somehow doesn’t get as much press as the first two. Aside from parishes where people are encouraged to wear red on Pentecost Sunday or where a catechetical group has a birthday party for the Church, we don’t see much to-do over this solemn feast. No one markets Happy Pentecost cards. Dollar Tree and Party City don’t have dove balloons or paper plates and napkins decorated with hovering tongues of fire. We just celebrated this feast on June 9, but no one traveled to Grandma’s and Grandpa’s for the express purpose of observing it.

While the Holy Spirit is present and referred to in one way or another from Genesis through Revelation, we just seem to have trouble saying who this member of the Trinity is. We have banners that go up in time for Confirmation proclaiming the seven gifts of the Spirit. We hear of fruits of the Spirit. And we utter the Spirit’s name with every Sign of the Cross, Glory Be, and Creed. But we puzzle.

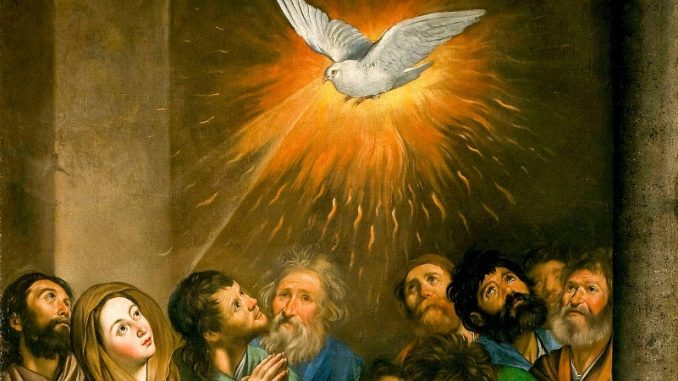

The Catechism of the Catholic Church speaks of the classic symbols of the Spirit: water, anointing, fire, cloud and light, seal (like the imprint on an important document), hand, finger, dove. That partially explains our challenge. None of these fits our idea of a person. We readily picture our Father-God, even though we know the Creator isn’t actually an ancient bearded man. We relate readily to God the Son in his humanity. But when someone tries to apply a human form to the Holy Spirit, it somehow falters. No matter how much people may have been fascinated by the artsy Asian woman who depicted the Holy Spirit in “The Shack,” the idea didn’t catch on.

Yes, we profess that the Holy Spirit is a person of the Trinity, active in the world and in us. But we more easily picture the intangible, bodiless action-packed personal force by the Spirit’s results.

The Holy Spirit is on the job when the prayerful, magisterial Church deliberates and decides. The Spirit is on the job too when we find ourselves saying or doing things that are wiser than we ourselves are. The Holy Spirit prompts, cajoles, warns, invites — a voice within that secret sanctuary residing within us. The Holy Spirit speaks in the words of Sacred Scripture in a way that stirs and sears us more than any other written work can and is invoked as the bread and wine are consecrated at Mass. But the Spirit is also silently summoned in our calmest moments on a river bank or in the darkest night.

The New Testament book following the Gospels is the Acts of the Apostles. Some students of Scripture have observed that it could rightfully be called the Acts of the Holy Spirit. That idea is both good and bad: good because it gives credit where credit is due, bad because it might imply that the Spirit’s actions are somehow past. Perhaps the best way we can personalize the Holy Spirit is to recall the wisdom of St. John Paul II, who, in his encyclical on the Holy Spirit, defined the Spirit as “personal love.” Wherever we see genuine, pure, self-giving love, the Spirit is there.