VATICAN CITY—After decades of anticipation, the Vatican archives are ready to welcome, starting March 2, scores of scholars wishing to study documents related to the wartime pontificate of Pope Pius XII.

All 85 researchers who have requested access have been given the green light to come and sift through all the materials from the period of 1939 to 1958, Bishop Sergio Pagano, prefect of the Vatican Apostolic Archives, told Catholic News Service Jan. 13.

Coming from at least a dozen countries, the first wave of researchers includes 10 experts from the United States, including two from the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. The museum has been working with the Vatican archives for more than a decade, Bishop Pagano said, ever since Pope Benedict XVI authorized the early opening of materials pertaining to the pre-World War II pontificate of Pope Pius XI.

So far, Bishop Pagano said, seven experts will be coming from Israel, 14 from Germany, 16 from Italy, 20 from Eastern Europe, including Russia, and the rest from France, Spain and Latin America to study the Pius XII-era archives.

“But we expect an increase in requests after March 2,” he added.

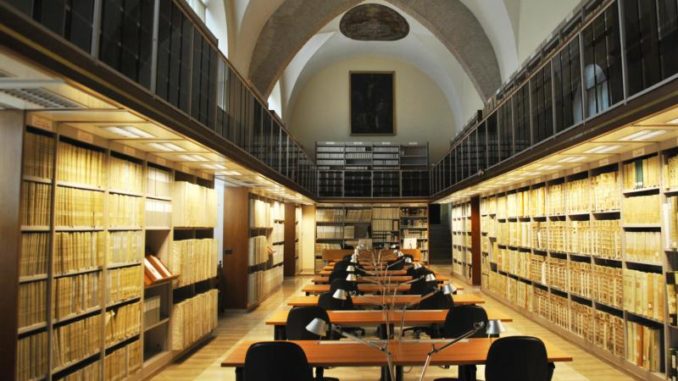

While the reading rooms and archive personnel can accommodate and assist a maximum of 60 people a day, the newcomers’ access will be staggered out over the year, he said, allowing the many academics currently pursuing other topics to continue their work. The archive’s records and artifacts date back more than 1,000 years and fill more than 50 miles of shelving.

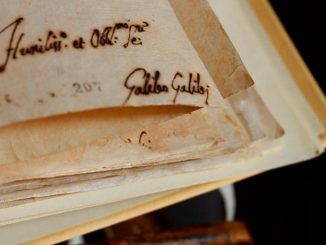

It took more than 12 years to sort through, organize and catalogue the enormous quantity of information from Pope Pius XII’s long pontificate, Bishop Pagano said; documents from the time period also were collected from the archives of the Vatican Secretariat of State, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and Vatican nunciatures around the world. The open collection also includes thousands of notes regarding Pope Pius’ charitable activity in Italy and abroad.

In fact, Bishop Pagano said he hoped there would be in-depth research into the critical and huge amount of aid the pope gave to those desperately in need during and after the war. Such massive assistance, he said, was due in large part to a constant flow of generous donations from the United States.

Just the index — listing the documents with detailing of who made the donations, the amounts sent and where the money went — takes up two volumes.

“There was not only a Marshall Plan,” the U.S. program for the economic recovery of Europe after World War II, he said, “but you could say there was also a U.S.-Vatican plan by American Catholics to help the pope in his enormous works of charity.”

The nationality or religion of those requesting aid did not matter to the pope, only verifying that need was legitimate, the bishop said.

He said the archives have letters from people who admitted they were atheists but were turning to the pope for help because they saw him as the only moral leader left in such a dark time in history.

Referring to accusations by some historians and Jewish groups that Pope Pius XII and others did not do enough to stop the Nazi rise to power and the Holocaust, Bishop Pagano said the pope “did speak with his efforts and then he spoke up with words, so it is not true that the pope was totally silent.”

The new researchers’ stated fields of interest, he said, obviously were focused on World War II, the Holocaust, the persecution of the Jewish people, the murder of Italian citizens in Rome by Nazi German troops and the relationship between the Holy See and the Nazi’s national socialist party and with communism.

But some are also looking into Pope Pius’ valuable theological legacy and writings. He wrote more than 40 encyclicals, and “he is one of the popes most cited during the Second Vatican Council,” the bishop said.

Some experts also will be looking for information about local dioceses and how the pope may have helped those sheltering refugees and Jews in religious institutes, for example, he said.

However, based on what he has seen, he said he does not think researchers will find anything “enormously new” or anything that will turn history “upside down.”

For years, historians have pored over information already available from national, local and private archives, he said.

The material now available in the Vatican archives should provide greater details and help historians “better analyze how certain processes were set in motion, how the pope studied certain issues, who analyzed them, which people contributed” to his way of proceeding, like the advisory role the Jesuits had both concerning world affairs and the pope’s encyclicals, Bishop Pagano said.

Together with what has been emerging in national archives, he said, “many prejudices (against the pope) will fade away, without a doubt.”

But, “it will take many years to form a new opinion about Pius XII. One, two years is not enough,” said the 71-year old bishop, who has worked at the archives for more than 40 years.

If studying all historical records is done objectively and critically, he said, “maybe in 10 years a new impression will take shape of this pontificate, which was very remarkable and came at a very critical point in world history.”

While everyone given access to the archives is a qualified and experienced researcher, “not everyone has a well-developed scientific approach,” the bishop added.

Some come looking for something that does not exist, and some are just curious. But those who are serious scholars know that it takes a very long time to look at many historical records and to cross-reference all of them.

“It’s not enough to have found one file that talks about one thing and then write a book because that file is related to 10 others in many other collections,” he said. “Therefore, my advice I would give scholars who come to the Vatican archive is to stay for a long time, the longest time possible” in order to take advantage of its unique holdings.

By Carol Glatz