When Sister Philomena tried to wrap the minds of second-graders around the concept of the Blessed Trinity, she used an egg. There’s the white, the yolk, and the shell, she explained, but it’s all one egg. Theologians might object that her egg wasn’t much better than a three-leaf clover or a triangle for getting at a sacred mystery, but it seemed to work for children, a few of whom still had their baby teeth. It wasn’t too likely that their pastor would be asking them about the immanent Trinity and the economic Trinity as they prepared for first penance and first Communion.

Their developing brains were not prepared to make distinctions about the interior life of the Godhead (the immanent Trinity) and those things having to do with the saving activity and our experience of the three persons (the economic Trinity).

The chances are that our brains aren’t either.

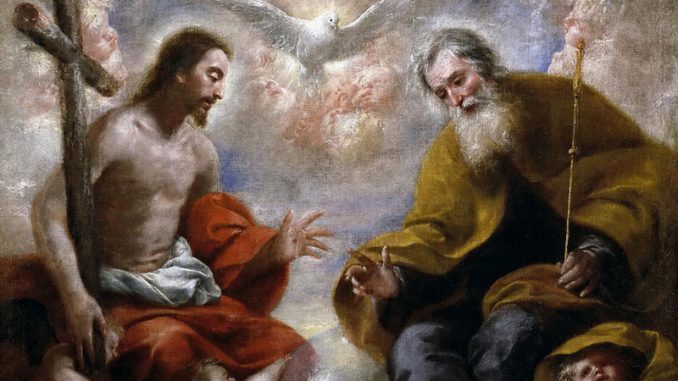

In all honesty, it’s the rare individual who puzzles over how the three persons of God are one as he or she makes the sign of the cross, says the Glory Be, or sings the Gloria. We take it on faith. Each of us has our own mental picture of God, the Three-in-One, but it seems that generally we pick and choose which person of the Trinity we pray to, usually according to our current issues or impulses.

When we are struck by beauty and goodness and are counting our blessings, we tend to praise and thank the Father. So, too, do we reach out to the Father when we feel in particular need of paternal love and protection.

We address Jesus as both Lord and brother, sure that he understands our human plight and can relate to our pain. We think of him as our teacher, companion on the journey, and as the exemplar of God’s mercy. And we recognize him in the Eucharist, as the disciples on the road to Emmaus did.

From school days on, many of us have tended to invoke the Holy Spirit at times of test-taking or simply at times that have tested our wills. We find ourselves in need of one or another of the seven gifts of the Spirit and pray for them, and we ask the Spirit for wisdom and guidance as we go through life’s minefields.

The fact that we advert to one person of the Trinity or another doesn’t mean, though, that the other two are missing in action. The Catechism of the Catholic Church reminds us that each of the divine persons is fully God and that the three persons act together. That having been said, the Catechism also notes that the persons have distinct roles: generation, salvation, and the imparting of the mission of the Son and the Spirit to the Church.

A priest friend who is now retired in Minneapolis-St. Paul once told me that a young couple had wanted him to baptize their newborn in the name of the Creator, the Redeemer, and the Sanctifier. Not surprisingly, he told them that he couldn’t do that. When they questioned him, he replied that we baptize in the names of the persons of the Trinity, not job descriptions!

That leads to a key insight that we Christians gain through our belief in the Trinity. God’s nature is personal and relational. The Catechism quotes a 5th century creedal statement saying that “God is one but not solitary.” This certainly ties in with St. John’s insistence that God is Love. The very nature of God is to be in relationship, to be pouring out love interpersonally.

Thinking about the relationality of God sends a special message to us. If we humans are made in the image and likeness of God, then it is in our nature — and it is our call — to be in relationship. That’s why we have family and community, and it’s clearly why we belong to and need Church.

As we celebrate Trinity Sunday, we have to admit that we live with and in ongoing mystery. There are so many things that are beyond our comprehension. But we can be sure that our lives are really all about love — and that adoring and communicating with our God is how we stay in love.