In this column I will be telling, in brief, the tale of two men — and more.

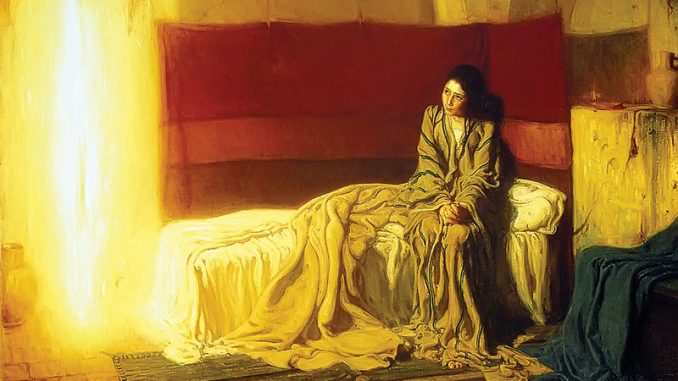

One of the masterpieces painted by Henry Ossawa Tanner is my all-time favorite depiction of the Blessed Virgin Mary. His “Annunciation” is on display in the 19th century American collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I have been there to view the original more times than I can count. His depiction of the young Hebrew girl facing the being of light whom we know as Gabriel is poignant and riveting.

Tanner was the son of a Pittsburgh minister who became a bishop. His innate talent was nurtured for a time at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts after he had been repeatedly refused as a student or apprentice by a number of artists and craftsmen. While the noted artist Thomas Eakins (famous for paintings of scullers on the Schuylkill, boxing matches, and so on) eagerly supported him, Tanner suffered abusive remarks, rough treatment, and was ostracized by a number of Philadelphians. His artistry and reputation soared when he moved to Paris and was embraced by artistic peers and masters. One of the Wanamakers of Philadelphia then funded a sojourn in the Mideast for him. Not surprisingly, many of Tanner’s most revered pieces have biblical themes.

Augustus Tolton, now a candidate for Catholic sainthood, was born in Missouri, but his family relocated to Illinois when the Civil War broke out. An Irish pastor, Peter McGirr, saw a prospective priestly vocation in Tolton and urged him to apply to one seminary after another, all of which refused him. Ultimately, Tolton was accepted and enrolled in the Pontifical University known as the Urbanum in Rome and was ordained there.

He returned to serve in the Archdiocese of Chicago, where he built a huge community of faith and a church and also exercised a vigorous pastoral ministry. An anonymous writer from Chicago has said this of the barriers which Tolton overcame: “Tolton dared to believe that no door can be kept closed against the movement of the Lord and the power of the Spirit.”

There are several common threads in the stories of these two men. One is their religious faith and their drive to witness to it in their varied vocations, one as an acclaimed painter, the other as an energetic priest. Another is the fact that they met with little acceptance and even outright rejection in the states, which caused them to refine their gifts and talents in Europe. A third is the fact that both were 19th-century African American males born into families touched by slavery and spent their childhood and youth amid the ravages of the Civil War and the hubbub of Reconstruction.

Unfortunately, 160-plus years after their births, we know that young African American men — and women — continue to suffer mistrust, the thwarting of hopes and dreams, persecution, assault, and, as we keep seeing, violent deaths. Racism is a sin, Catholic bishops and popes agree and have said so, but it is so deeply entrenched in the American psyche that we seem unable to hear or internalize this truth.

At every turn, we are faced with questions of what needs to change and what we can do. What needs to change is clearly systemic, and laws and courts must support racial justice. But having protections on the books does not heal hatred any more than totalitarian regimes or restrictive legislation managed to keep Serbs and Bosnians or Hutus and Tutsis or many, many others from allowing old grudges and prejudices to fester and explode into genocide within the last 30 years. There are good reasons why many of us cringe when we find ourselves riding on secondary roads alongside a truck flying a Confederate flag and bearing an obvious gun rack.

Collectively, for sure, we can uphold the right to life, from womb to tomb, of our neighbors, all of them. And we can join with them in efforts on behalf of what the U.S. Constitution calls the general welfare and Catholic moral law calls the common good.

We can be agents of change by the way we act and react together. Individually, we who benefit from white privilege (willingly or unwillingly) can befriend persons of color and step out to defend their rights to equal access, equal education, and equal privilege. When we have the opportunity to promote, sponsor, and encourage the gifts of persons of color we can do so with dollars and our demands.

On the whole, though, we will only undo the long legacy of racism by changing hearts. It takes prayer and concrete action — and may require exorcism. We cannot afford to lose geniuses like Tanner, saints like Tolton, or ordinary men and women because we don’t assure that they can breathe, jog, or spend their nights in peaceful sleep.