Some years ago my brother Steve was sent on overseas jaunts to create text for promotional brochures for his then-employer, a travel agency. Several of them allowed for side trips into less inhabited areas, along with the sought-after cities and tourist destinations.

After one such sojourn in Peru, he returned with a gift for me: a framed 8”x10” color photo of a primitive bamboo structure with a handmade lopsided sign hanging over a makeshift entryway. The sign read “Iglesia Catolica” — Catholic Church.

That photo brings to mind something we discover as we delve into the history of our now 200-year-old diocese. Catholics have always managed to make do when it comes to worship spaces. When we build and decorate chapels and churches meant to last, we always make every effort to appoint them well and use precious materials.

But when we don’t have means, we figure out how to gather those who share our faith.

It is fairly well known that the first church built in Charleston was constructed while we were still part of the Diocese of Baltimore: St. Mary’s of the Annunciation, founded in 1789.

It was the only church in what became the tri-state diocese handed to Bishop John England in 1820. Before that, we can cite the evidence that a designated chapel with a resident priest was located at Santa Elena, the Spanish settlement at what is now Parris Island. The settlement lasted only 21 years, however, from 1566-1587. So where did Catholics gather?

For one thing, through much of the 16th, 17th, and early 18th centuries, Catholics were few and far between. Labeled “papists,” Catholics endured outright persecution.

Bishops from Havana, Santo Domingo, or other locales periodically traversed our territory to administer the sacrament of confirmation. Jesuits and Franciscan and Dominican friars were among itinerant priests who appeared to baptize, hear confessions, celebrate Mass, and witness sacramental marriages.

Sometimes Quaker men traveling through what was then still a colony were suspected of being priests in disguise. Always under a cloud of suspicion, Catholics were an outright oddity.

Even after the United States became an independent nation and the Constitution and the Bill of Rights assured the free practice of religion and no “religious test” for those who might hold office, most of our far-flung Catholics were not equipped to establish churches.

So where did they congregate?

Catholics in South Carolina, from the earliest days and throughout the 20th century, often worshiped in some unexpected places. True, by the 19th century Catholics began to put together temporary structures and eventually build small churches, such as we can find today in places like Allendale and Cheraw. But, often enough, they used the model of the “house church” which we find in the Acts of Apostles and the epistles. In the first century of Christianity, we hear of early Christians meeting in the home of John Mark’s mother, in Chloe’s house or Nympha’s or Lydia’s as the preaching of the apostles expanded.

Our diocesan history tells a similar story. In the early 19th century, the French-born Nathalie de Lage Sumter, daughter-in-law of Revolutionary War hero Thomas Sumter, held catechetical classes, and, on Sundays, when a priest could not be had, she conducted what were termed “dry Masses” (readings and prayers) in her home.

During the Civil War and Reconstruction era, the African American Catholics of Ritter, now called Catholic Hill, were held together by a man called Vincent de Paul (or Vincent of Paul) Davis, who likely used homes and open spaces.

In Bluffton, when a priest was on hand, the Pinckney family hosted Mass in their dining room and eventually built a small chapel. Dr. Burt of Edgefield had a family chapel. The Morgan home in Georgetown was a worship site, as was the Herlihy home on Edisto Island, the Francis home in Lancaster, and the Purcell home in Newberry — just to offer a few examples.

There were also pastors of other denominations who cordially opened their doors, despite the persistence of anti-Catholic rhetoric and sentiment. As early as the 1820s, Bishop England noted that Episcopalians, Methodists, and Lutherans frequently lent him space to gather the scattered Catholics of his diocese. Up until the present day, we find that other denominations have lent space to Catholics to serve as temporary worship sites or schools.

Lutherans in Mauldin, Mount Pleasant, Goose Creek, and Spartanburg were among those who accommodated Catholic neighbors. St. Mary Magdalene in Simpsonville benefited from the nearby Ebenezer United Methodist Church. A non-denominational church, River Hills, let Catholics use its premises before All Saints in Lake Wylie was built. In our 21st century, John Paul II School in Ridgeland started its first year in Sunday school classrooms belonging to Okatee Baptist, and St. Elizabeth Ann Seton in Myrtle Beach opened at St. Mark Coptic Orthodox Church.

Some other locations used for worship demonstrate Catholic adaptability — while at times inviting head-scratching. St. Ernest Mission in Pageland started out at Kay Owens’ home but had to move to a turkey hatchery as the number of Catholics grew. The parishioners of St. James, Conway, initially met in a hotel lobby and VFW hall, while St. Joseph Mission, Darlington, started at the American Legion. St. Francis by the Sea, Hilton Head, made use of the First Presbyterian Church on Saturday evenings and Crazy Crab Restaurant for Sunday and weekday Masses. Holy Cross Mission at St. Helena Island migrated from Kinard’s store to a local gas station and then to Mrs. Mungin’s Soul Palace before it settled at its present site on Seaside Road.

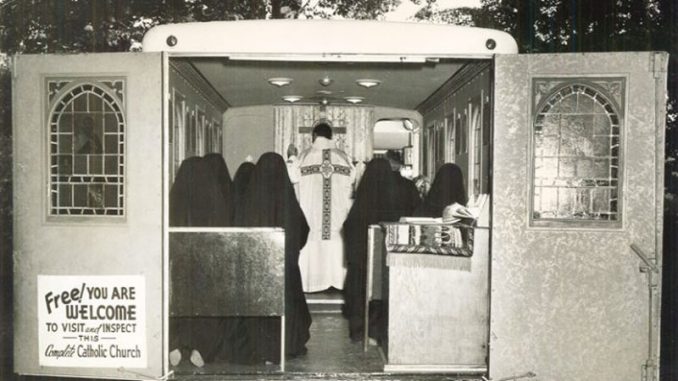

Perhaps most interesting of all is Father Patrick Quinlan’s “church on wheels,” a large truck refurbished with Gothic windows and interior pews and altar, which traversed Williamsburg County and appeared at both sessions, white and black, of the segregated state fair.

Father Quinlan, now under consideration for sainthood, had a decades-long mid-20th century catechetical ministry called the Catechumenate of Our Lady of Fatima. His ministry invited parishioners and interested parties to abandoned stores, a dance hall, and his sanctified eighteen-wheeler.

What all this adds up to is that Catholics know they need community, need worship space, and somehow find it or create it. We always have — and do. So now we’re masked, socially distanced, and also livestreaming. That’s our latest Catholic way of making do.