WASHINGTON—The nationwide reckoning on racial justice spurred by cases of police killing unarmed Black men and women should impel Catholics to learn about racism and its history in the church and to draw on their faith to take action to combat it, panelists said during an online discussion.

They also emphasized the importance of learning the history of U.S. Black Catholics who endured slavery, segregation and racism in society and the Catholic Church and who kept their faith.

Racism and systematic racial injustice “are the issues our people are trying to navigate and are struggling with,” said Father Robert Boxie III, a priest of the Archdiocese of Washington, who is the Catholic chaplain at Howard University.

He said it was important for Catholic bishops and priests to offer guidance on this, and for the faithful to “become well-informed, intentional Catholics who actually go and do something about this grave sin of racism we are experiencing.”

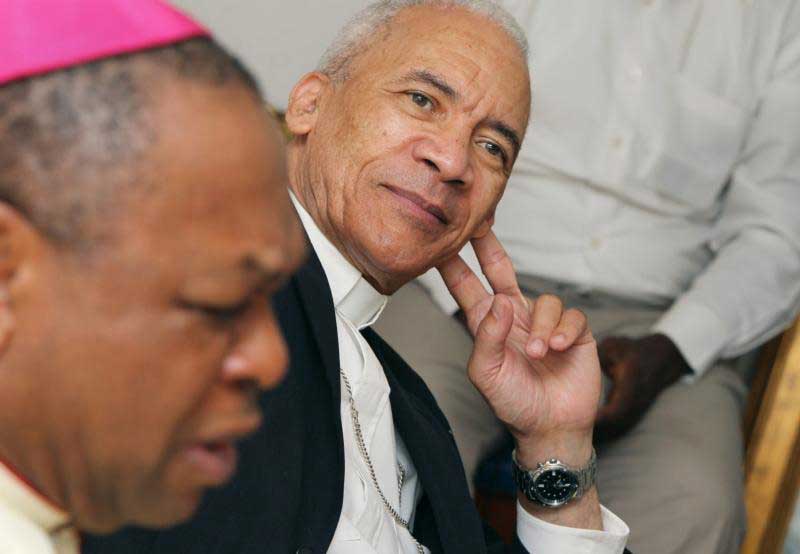

Father Boxie and three other Black Catholics spoke on an Oct. 13 panel on “Religion and Race: The Future of Anti-Racism and the Catholic Church” during a livestreamed Salt and Light Gathering for young adults. It was sponsored by Georgetown University’s Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life and by the Archdiocese of Washington’s DCCatholic young adult ministry’s Theology on Tap program.

Moderator Jonathan Lewis, the archdiocese’s assistant secretary for the Secretariat of Pastoral Ministry and Social Concerns, noted the racial justice movement sparked by the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and asked the panelists how the Catholic Church should confront the issue of racism.

Taylor, an emergency medical technician, was shot to death by Louisville police on March 13 during a nighttime raid on her apartment, and Floyd died on May 25 after a Minneapolis police officer knelt on his neck for almost nine minutes during an arrest.

“For my kids and many kids of color, the death of George Floyd was just another reminder of the first few years of their lives,” said panelist Gerald Smith Jr., principal of St. Thomas More Catholic Academy in Washington. “My kids in the eighth grade can name a victim that has been killed by police brutality.”

The principal added, “For them, it was normal. If I’m called to work with some of the youngest, most marginalized groups of people, and if they have this thought that this is normal, we need to do something about it.”

Smith said their school tries to teach its young scholars to respect other people and cultures, especially the marginalized, and to have an awareness of the world around them and know they have the power within themselves to take action against injustices in society.

“One of the greatest things we do as Catholics is discernment. … We should practice that often,” he said, noting that is essential in confronting systems and policies that are racist and reflecting on what it means to be anti-racist.

Another panelist, Ogechi Akalegbere, a Nigerian American who serves as the Christian service coordinator at Connelly School of the Holy Child in Potomac, Maryland, said, “I call myself an activist and a social justice warrior.”

She emphasized that Catholics need to get out of their comfort zones and be advocates for those who are on the margins, walking as allies beside brothers and sisters of color who are facing injustices.

Akalegbere, who is the content creator for the podcast “Tell Me, If You Can,” said it is not enough for Catholics to just think they are not racist.

“You have to take on the fight. You cannot be passive. You can’t be on the fence,” she said, adding that as people learn about racism, they should talk with others about it, including their family members, even if broaching the topic brings discomfort.

She noted, “If you ever feel comfortable working toward racial justice, you’re not doing it right.”

Panelist Shannen Dee Williams, an assistant professor of history at Villanova University, said it “is important for every Catholic to understand that the Catholic Church was never an innocent bystander in the history of slavery, segregation and exclusion in American society.”

She noted that at times in American history, the church was “the largest corporate slaveholder in Florida, Louisiana, Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri.”

Williams, who has a doctorate in history from Rutgers University, pointed out how noted early figures in U.S. Catholic history likewise are connected to slavery and racial injustice.

“There is a Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence – Charles Carroll of Carrollton – who was one of Maryland’s largest slavers, who was also the cousin of Bishop John Carroll, who was our first bishop and who was himself a slave holder,” she said.

She also noted how Roger B. Taney, the nation’s first Catholic Supreme Court justice, wrote the infamous Dred Scott decision in 1857.

That decision, she said, claimed “Black people ‘had no rights which the white man was bound to respect,'” and denied the freedom petition of Scott, his wife, Harriet, and their two daughters.

In the years following emancipation, Black Catholics faced segregated churches and schools and encountered barriers that prevented them from entering segregated seminaries and religious orders. Williams noted that some Catholics adopted an adversarial position toward the freedom struggle of Blacks during the civil rights movement.

“Obviously, racism is real. White supremacy is real in our history, and it’s also real in our church,” she said.

But Williams said it also is important to remember the stories of Black Catholics who lived out their church’s teachings on human dignity and serve as a “moral compass” in their times and ours, like Martha Jane Chisley Tolton, the mother of Father Augustus Tolton, who led young Augustus and her two other children in escaping from slavery in Missouri to freedom in Illinois.

“It is this family that will give us our nation’s first self-identified Black priest,” she said of Father Tolton, who was ordained to the priesthood in 1886 and later served as a parish priest in Chicago before his death in 1897.

Father Tolton, one of six U.S. Black Catholics whose causes for sainthood are under consideration, was recognized as living a life of heroic virtue and was declared “Venerable” by Pope Francis in 2019.

The other sainthood candidates are: Pierre Toussaint, who was born a slave in Haiti and became a noted for his works of charity in New York City and declared “Venerable in 1996; Mother Mary Elizabeth Lange, foundress of the Oblate Sisters of Providence; Mother Henriette Delille, foundress of the Sisters of the Holy Family and declared “Venerable” in 2010; Julia Greeley, a laywoman in Denver known for acts of charity, who died in 1918; and Sister Thea Bowman, a Franciscan Sister of Perpetual Adoration, who was a noted evangelist who died in 1990.

Father Boxie, like the other panelists, underscored the importance of learning those instances of racism in the church’s history and the story of Black Catholic history, and he said that should be part of the formation in seminaries and the ongoing formation of priests.

“When we acknowledge what the church has done, her failures, her shortcomings, we arm ourselves with the power to move forward and do something about it,” he said.

By Mark Zimmermann, editor of the Catholic Standard, newspaper of the Archdiocese of Washington.