Let us hope that, as this column is read, we are not embroiled in something like the hanging chads fiasco of the Y2K American presidential election. Or something worse.

To put it far too mildly, there has been heightened anxiety about this election and its possible aftermath, short-term and long-term. The challenge before us is keeping faith and equanimity no matter the outcome.

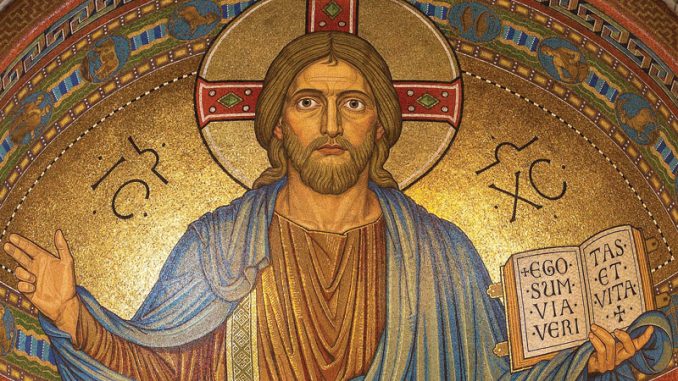

When we look to our Christian tradition, we have to recall that Jesus counseled us to “render to Caesar,” even while he was well aware that Caesar had henchmen who enforced their laws and wills by crucifixion.

In St. John’s account of Jesus’ interaction with the cowardly pagan Pontius Pilate, Jesus reminds Pilate that he would have no power or authority if it had not been “given from above.” The long history of Christianity shows that, for the most part — with the possible exception of some years of what was called the Holy Roman Empire — followers of Christ have been under the authority of all sorts of governors and governments which did not necessarily subscribe to Biblical and religious standards.

We Christians have had to cooperate with civil authority, show respect, pay taxes, serve and protect our countries, and obey laws unless they defied our consciences and commanded evil.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church reminds us that the commandment to honor one’s father and mother also applies to civil authority, whether or not that authority ends up being one we would prefer. The commandment not to kill obviously applies to refraining from abortion, euthanasia, the killing of innocents, murder in general, but it also has corollaries.

Included among these are what the Catechism calls “safeguarding peace,” and peace is described as maintaining “respect for the dignity of persons and peoples, and the assiduous practice of fraternity. Peace is the work of justice and the effect of charity.” The Catechism also issues a grave warning against fomenting anger, hatred, and violence.

Living these moral obligations is not always easy. Some have worn shirts, hats, and buttons and sported bumper stickers which might suddenly seem anti-climactic and might spur on resentments. But, whatever the outcome of elections, we cannot revert to voter rage. We might, instead, realize that we have to learn some lessons.

One is that no political leader and no political party can be regarded as Messiah and Lord. Our bishop reminded us, in a video made this fall, that “We are not Republicans; we are not Democrats. We are Catholics.” We have had the obligation to vote according to well-informed consciences, and that is what we hope all believers have done. Beyond that, we have to remember that the most effective revolutions have been won by changes of heart. Our duty as missionary disciples, which is what all baptized persons are called to be, is to transform the world. We are to help it conform more closely to the Kingdom of God by our attitudes and behaviors, by our example and ideals, by our prayer and by our work.

Abortions may be limited by legislation, but the will and desire to abort is only altered with a change in consciousness and conscience. Immigrants, migrants, and refugees may find their situation eased by judicial decisions or legislative action, but resentments and severe treatment are not remedied without a depth of love and compassion for the stranger.

Certain racial injustices may be curtailed by a Civil Rights Act, but prejudice is not healed unless we enter into the lives and loves and experiences of one another. We can cite some saintly insights to help us attain the civility that can lead us to behave well as citizens and as followers of Jesus.

St. Augustine, in his famed City of God, asked, “Remove justice, then, and what are kingdoms but large gangs of robbers?” He observed that the “City of Man” does not typically conform to the characteristics of God’s Kingdom. He acknowledged the Roman Empire’s valuing of glory and domination and contrasted it with the Christian’s call to self-giving and mercy. The Christian citizen, he said, is one who seeks “ordered concord” in his or her family and does all in his or her power to contribute to “civil peace” and order. Who is the citizen who does that?

The Christian, St. Augustine said, who subscribes to the injunction to “injure no one” and “do good to everyone he can reach.” Human nature, when it is heeded and honored, St. Augustine said, directs us to maintain relationships with all, even those we might regard as wrong-headed or downright wicked.

In more recent times, we have had many models of holy people who have lived this dictum. St. John Paul II reached out to Communist leaders as well as their opposition in the Solidarity movement. Walls fell, with the agency of the Holy Trinity, the intercession of the Blessed Mother, and the prayers of millions. As Holy Father, he also visited and conferred at length with his would-be assassin, and that assailant sent him a thoughtful get well card when he was in his final illness and also attended his funeral.

Servant of God Dorothy Day, who co-founded the Catholic Worker after her conversion from atheistic Communism, declared, “I really only love God as much as I love the person I love least.” St. Teresa of Calcutta urged, “Let us not use bombs and guns to overcome the world. Let us use love and compassion. … Keep the corners of your mouth turned up. Speak in a low, persuasive tone. Listen; be teachable. Laugh at good stories and learn to tell them. … For as long as you are green, you can grow.”

Underlying the insights and example of these holy people is the basic message of Jesus Christ, in both his teachings and example. The world is won over when one realizes that the Good Samaritan might be the person one would initially judge to be one’s natural enemy. The one who will be welcomed in Abraham’s bosom can be the beggar at the gate rather than the comfortably housed and fed person inside. The beloved may be the public sinner who washes feet rather than the one who knows every precept and canon by heart.

And, as I have learned very recently, the person with whom I may have a surprising affinity can be the A.M.E. pastor who lives within walking distance of my convent and the rabbi who has a synagogue across the bridge.

We don’t agree on certain core points of doctrine or in certain moral-political judgments, but we can build upon ideals which unite us on behalf of the common good.

As we all can see, the common good of this nation demands that we do better in so, so many ways. Love is all that wins — because, as St. John insists, God is love.