The feast of the Epiphany of Our Lord is celebrated throughout most of the world on Jan. 6, 2021. In the United States, the Solemnity is celebrated either on Jan. 6 or, according to the decision of the episcopal conference, on the Sunday between Jan. 2 and Jan. 8. This year, that date fell on Jan. 3.

The word “epiphany” comes from the Greek epiphainen, a verb that means “to shine upon,” “to manifest,” or “to make known.” The feast of the Epiphany celebrates the many ways that Christ has made Himself known to the world. There are three main revelatory events that manifested the mission and divinity of Christ: the visit of the Magi (Matthew 2:1-12), the baptism of Jesus (Mark 1:9-11), and the miracle at Cana (John 2:1-11).

The visit of the Magi is emphasized on Epiphany Day, and Christ’s baptism is celebrated the first Sunday that follows.

This feast marking the end of Christmas is called “Epiphany.”

Why is Epiphany celebrated 12 days after Christmas?

In the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church, Epiphany celebrates the revelation that Jesus is the Son of God and savior of the world.

Christians believe that the 12 days of Christmas mark the amount of time it took after the birth of Jesus for the magi, or wise men, to travel to Bethlehem for the Epiphany, when they recognized him as the son of God.

Epiphany also celebrates the baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist in the Jordan, and the wedding feast at Cana in Galilee.

In the Eastern rites of the Catholic Church, Theophany — as Epiphany is known in the East — commemorates the manifestation of Jesus’ divinity at his Baptism in the River Jordan.

While the traditional date for the feast is Jan. 6, in the United States the celebration of Epiphany is moved to the next Sunday, overlapping with the rest of the Western Church’s celebration of the Baptism of Christ.

However, the meaning of the feast goes deeper than just the bringing of presents or the end of Christmas, said Father Hezekias Carnazzo, a Melkite Catholic priest and founding executive director of the Virginia-based Institute of Catholic Culture.

“You can’t understand the Nativity without Theophany; or you can’t understand Nativity without Epiphany,” he said. The revelation of Christ as the Son of God — both as an infant and at his baptism — illuminate the mysteries of the Christmas season, he said.

“Our human nature is blinded because of sin and we’re unable to see as God sees,” he said. “God reveals to us the revelation of what’s going on.”

Origins of Epiphany

While the Western celebration of Epiphany (which comes from Greek, meaning “revelation from above”), and the Eastern celebration of Theophany (meaning “revelation of God”), have developed their own traditions and liturgical significances, these feasts share more than the same day.

“The Feast of Epiphany, or the Feast of Theophany, is a very, very early feast,” said Father Carnazzo. “It predates the celebration of Christmas on the 25th.”

In the early Church, Christians, particularly those in the East, celebrated the advent of Christ on Jan. 6 by commemorating Nativity, Visitation of the Magi, Baptism of Christ and the Wedding of Cana all in one feast of the Epiphany. By the fourth century, both Christmas and Epiphany had been set as separate feasts in some dioceses. At the Council of Tours in 567, the Church set both Christmas day and Epiphany as feast days on the Dec. 25 and Jan. 6, respectively, and named the 12 days between the feasts as the Christmas season.

Over time, the Western Church separated the remaining feasts into their own celebrations, leaving the celebration of the Epiphany to commemorate primarily the Visitation of the Magi to see the newborn Christ on Jan. 6. Meanwhile, the Eastern Churches’ celebration of Theophany celebrates Christ’s baptism and is one of the holiest feast days of the liturgical calendar.

Roman Tradition to celebrate Epiphany

The celebration of the visitation of the Magi — whom the Bible describes as learned wise men from the East — has developed its own distinct traditions throughout the Roman Church.

As part of the liturgy of the Epiphany, it is traditional to proclaim the date of Easter and other moveable feast days to the faithful — formally reminding the Church of the importance of Easter and the resurrection to both the liturgical year and to the faith.

Other cultural traditions have also arisen around the feast. Dr. Matthew Bunson, EWTN senior contributor, spoke about the “rich cultural traditions” in Spain, France, Ireland and elsewhere that form an integral part of the Christmas season for those cultures.

In Italy, La Befana brings sweets and presents to children — not on Christmas, but on Epiphany. Children in many parts of Latin America, the Philippines, Portugal, and Spain also receive their presents on “Three Kings Day.”

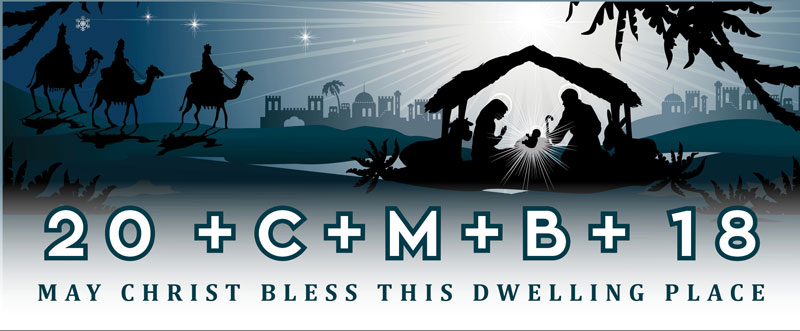

Meanwhile, in Ireland, Catholics celebrate “Women’s Christmas” — where women rest from housework and cleaning and celebrate together with a special meal. Epiphany in Poland is marked by taking chalk — along with gold, incense and amber — to be blessed at Mass. Back at home, families will inscribe the first part of the year, followed by the letters, “K+M+B+” and then the last numbers of the year on top of every door in the house.

The letters, Bunson explained, stand for the names traditionally given to the wise men — Casper, Melchior and Balthazar — as well as for the Latin phrase “Christus mansionem benedicat,” or, “Christ, bless this house.”

In nearly every part of the world, Catholics celebrate Epiphany with a Kings Cake: a sweet cake that sometimes contains an object such as a figurine or a lone nut. In some locations, the lucky recipient of this prize either gets special treatment for the day, or they must then hold a party at the close of the traditional Epiphany season on Feb. 2.

These celebrations, Bunson said, point to the family-centered nature of the feast day and of its original celebration with the Holy Family. The traditions also point to what is known — and what is still mysterious — about the Magi, who were the first gentiles to encounter Christ. While the Bible remains silent about the wise men’s actual names, as well as how many of them there were, we do know that they were clever, wealthy, and most importantly, brave.

“They were willing to take the risk in order to go searching for the truth, in what they discerned was a monumental event,” he said, adding that the Magi can still be a powerful example.

Lastly, Bunson pointed to the gifts the wise men brought — frankincense, myrrh and gold — as gifts that point not only to Christ’s divinity and his revelation to the Magi as the King of Kings, but also to his crucifixion. In giving herbs traditionally used for burial, these gifts, he said, bring a theological “shadow, a sense of anticipation of what is to come.”

By Adelaide Mena

This article was originally published on CNA Jan. 6, 2017.