WASHINGTON—No one has to tell Catholic school teachers how different this past year has been.

At the start of the pandemic last spring, most Catholic schools adapted to online schooling and continued that way until the end of the school year.

At the start of this school year, many of these schools across the country reopened in person, with multiple safety protocols in place, or they operated under a hybrid model with some students attending classes in person and other students in class virtually.

Pandemic learning impacted Catholic preschools to high schools across the country and its success seemed to hinge primarily on the flexibility of students and teachers alike.

That’s why it’s not surprising the topic of pandemic learning was a theme of so many of the workshops offered during this year’s annual National Catholic Educational Association convention April 6-8. Even the convention, which often draws thousands of participants, was virtual for the second year in a row, due to pandemic restrictions.

At the start of the online convention with participants joining in from all 50 states, retired Bishop Gerald F. Kicanas of Tucson, Arizona, who is chairman of NCEA’s board of directors, thanked Catholic educators in a video message for how they “stepped up in the midst of the pandemic” saying their enthusiasm and creativity enabled many schools to keep going.

Los Angeles Archbishop José H. Gomez, president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, similarly thanked Catholic educators in an April 7 message to convention participants where he noted the challenges of the past year and thanked teachers and principals for their response, which he said was a “testimony to your faith.”

Workshops focused on best practices in the pandemic, remote assessment of students, plans for students not returning next year and learning gaps during COVID-19.

One April 6 workshop highlighted what schools might keep from their virtual learning experiences and what they might not.

“We’ve had a year,” said presenter Michelle Lia, co-director of the Greeley Center for Catholic Education at Loyola University Chicago, reminding educators they likely had some “some amazing Hail Mary saves” and many opportunities to think on their feet.

When she invited the online participants to respond in the chat section with a few words to describe what they learned in the past year, responses included “flexibility” (several times), “patience,” “grace,” “humor” and “adaptability.”

One educator said they had been stretched this year, another said they were tired.

Lia said she has heard a fair amount of criticism from students and parents about busywork homework during the pandemic and said that going forward, “Google-able” homework, where students can find the answers online, should be eliminated.

But she also noted: “Technology is here to stay and it can be our friend,” noting students might be able to attend school virtually if they have a long illness and that parent-teacher conferences, which seemed to work better on Zoom, also might continue.

Teaching students who are virtually learning requires teachers to be very clear about their expectations, which of course should also continue, Lia said.

Another April 6 workshop on pandemic learning was led by a panel of teachers and principals from the Chicago Archdiocese and Julie Ramski, director of early childhood education for the Archdiocese of Chicago’s Office of Catholic Schools.

Ramski said when Chicago Cardinal Blase J. Cupich announced last summer that Catholic schools would reopen in person in the fall, this initially caused a lot of anxiety.

She said she spent a lot of time doing her own research and talking to teachers to reassure them they could do this.

“I kept saying, ‘if you’re all right, the kids will be all right,'” she said, adding she was convinced the best place for these students was to be in the classroom, with schools following numerous safety protocols.

The preschool teachers and elementary school principals told their online audience, many of whom went through much of the same experience, about keeping young students socially distanced and masked.

For preschoolers, it was important that they had more personal space and weren’t sharing crayons or other supplies, something that will continue in the future, these teachers said.

They also said they will likely continue Zoom parent-teacher conferences as these were convenient for both groups and they would absolutely continue with the safety protocols already in place, especially the daily cleaning of classroom surfaces.

“We are going to keep up (these practices) for the coming school year,” said Denise Spells, principal of St. Ethelreda School in Chicago, noting that if you change policies and then have to go back to them, it is confusing.

“Let’s just keep working with what’s working for right now,” she said.

“There are so many things you can do, so just drop the negative of what you can’t do and your whole experience will be much, much better,” Lisa Abner, a preschool teacher at St. Benedict’s School just outside Chicago, told the online workshop participants.

And amid all the challenges and new ways of doing things for teachers and principals, there have also been lessons for students that likely won’t come up on any assessment tests.

Martha Holladay, who teaches Advanced Placement English literature and composition at Padua Academy, a girls Catholic school in Wilmington, Delaware, said her students are learning what they need to and also are “learning intangibles.”

“They’re learning gifts of the Holy Spirit. They’re practicing wisdom, fortitude, self-control, other-centeredness, resilience. These are all things that we want our children to learn, and they are learning it,” she told Catholic News Service March 30.

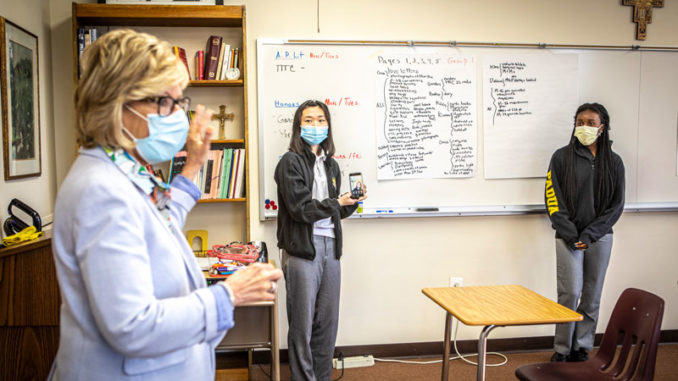

Holladay, like other teachers at Padua Academy, has been teaching a hybrid format since the fall. Some students are there in person while others are attending virtually, often by FaceTime on other students’ phones, which are moved around the classroom so the virtual students are included in every discussion and activity.

She said if someone told her decades ago she would be teaching this way, she wouldn’t have believed it, but the experience has taught her “that these girls are flexible, they’re resilient. They want to learn, and they really want to be good people.”

“That encourages me,” she added. “It gives me hope.”

By Carol Zimmermann

Contributing to this story was Chaz Muth in Wilmington