CHARLESTON—Joseph P. Riley entered politics to be a bridge builder, and he has been doing just that for 40 years.

In 1975 when Riley was first elected mayor, Charleston was a very different place. One of the biggest issues was the high crime rate on the downtown peninsular that was driving people out in droves.

Whoever was elected, change was on the way. Riley said he didn’t want that change to be hard-nosed and divisive, with police helicopters patrolling the skies; instead he wanted to find solutions that merged communities and bridged the chasm between black and white.

“I wanted to give everyone a voice,” he said. From the beginning, it was a community effort.

Parks and recreation flourished, providing a positive outlet for youth; jobs were created; and programs were instituted that formed relationships between police and the community they served.

“The citizens of Charleston were receptive to change,” he explained. “We went through this journey together — this journey of inclusion and equality and full partnership in government.”

It hasn’t been easy, and certainly there have been changes that some do not like, such as gentrification and the loss of small businesses; but overall, unity has prevailed, and become this city’s salvation.

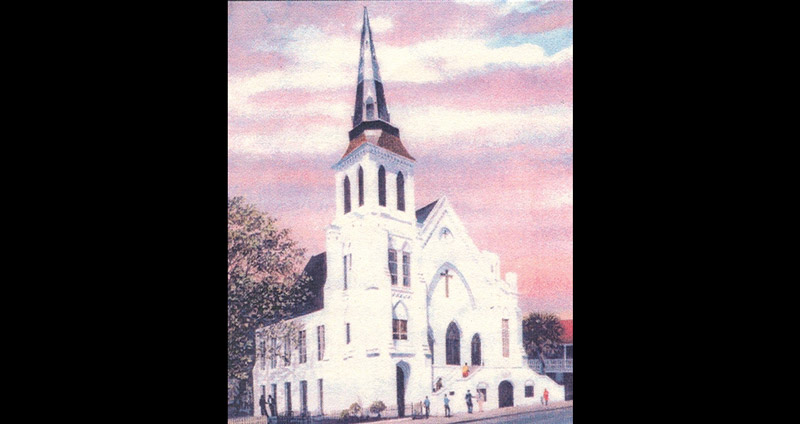

Last month, when a white gunman, warped by the whisperings of evil, entered a black church and killed nine men and women, the nation cried out. This was racism’s darkest heart exposed and many expected a violent outburst in response.

But that didn’t happen.

Instead, the community poured forth with comfort and prayers, and the grieving families offered forgiveness to the accused killer.

“They were grieving and crying and wanting to hug someone,” Riley said of everyone who came out. “There was just no place in this city for someone who wanted to take advantage of a tragedy like this.”

Groups looking to divide and separate found no foothold, he said. For Riley, it was affirmation of all he believes in — an amalgamation of races.

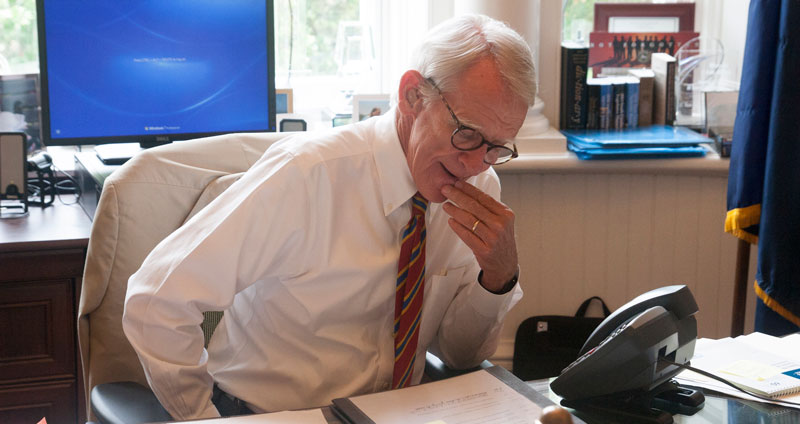

At 72, the small-statured, white-haired mayor sits at his desk, sunlight streaming through a large bank of windows. He is surrounded by family photos and mementos of his 10 terms in office.

In his youth, he said he was formed in great part by his Catholic faith and the times in which he grew up — a time of segregation and the fight for Civil Rights.

Riley often tells the story of when he was young and was told not to say “Yes sir” to a black man. It stuck with him and chafed him because it revealed two sets of rules, and he didn’t think it was right.

His formation started with Catholic education that emphasized the Gospels and the teachings of Christ that set forth life’s ethical principles, he said.

“It’s not possible to separate” faith and politics, or faith and anything, Riley said. “Your faith permeates you — your spirit, your perspective — so it’s just a part of me.”

He attends Mass on Sundays, serves as an extraordinary minister of holy Communion and lector, and takes up the collection.

He was also strongly influenced by the voices of his generation. A huge baseball fan, Riley grew up cheering for legends such as Jackie Robinson and Hank Aaron. In politics, he was drawn to John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr.

“I was exposed to the opportunity to think about the correctness … of how African Americans were treated,” he said. “I found myself becoming more assertive and interested in racial progress.”

As mayor, his progressive approach was quietly but implacably woven into the fabric of city life.

Dylann Roof, the confessed gunman in the church shootings, tried to unravel that unity.

When asked what was in his heart after learning of the nine deaths, Riley thinks for a very long time before offering one simple, stark word: Pain.

He refers to Roof as a bigoted, evil man, and mourns that level of hatred. “We all have a part,” he said, in erasing racism from our culture.

As he talks, Riley’s voice rolls along slowly and thoughtfully, but there are times when his sentences become shorter and sharper, and there is steel beneath that soft Southern accent. This is especially evident when it comes to the Confederate flag, a symbol that Roof used in his racist online posts.

“The flag is coming down,” he said, with emphasis. “The time has come. This tragic event was the last straw. We must move forward.”

The mayor attended the ceremony in Columbia on July 10 when the flag was removed, standing with family members of the nine people shot at Emanuel AME Church.

It was a moment of healing that many hope will continue forward.

“It’s an opportunity for all of us to examine ourselves and our attitudes and resolve in our own way we live our lives to seek to help our country do a better job — a decidedly better job — respecting, understanding and loving people who are different,” Riley said.