During the weeks after September 11, 2001, my religious community’s motherhouse hosted a series of evening prayers. Their culmination was a gathering of roughly 600 people to hear a Muslim imam and the local Catholic pastor join in a time of mourning and faith-exchange.

The imam came from nearby. He was in charge of a school and worship hall located where there once had been St. Stanislaus Church— one of five parishes in a small coal town that had been consolidated. Needless to say, having Muslims in our area was a novelty in itself. In the post-9/11, days inviting one of their leaders to a big convent chapel was even more of a curiosity. There was no sensationalism, however, in what the imam said. Instead, he offered a humble exposition of what he understood to be the true tenets of his faith.

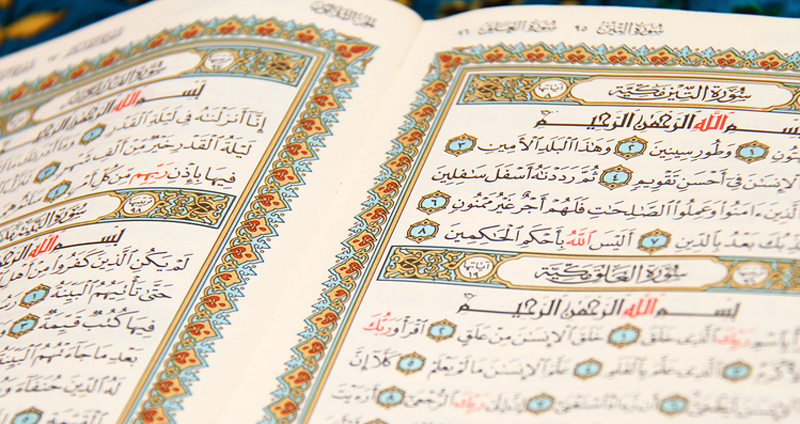

Before I summarize some of his comments, I should add that I have read the Koran. When I was a seminary professor, I joined a Christian- Jewish-Muslim discussion group that met regularly in Detroit. So, I had some basis on which to verify his credibility. I have been rereading the Koran to double-check the discussion.

Essential to Islam is belief in the oneness of God. Muslims don’t accept the idea that the one God could also be three-in-one. Allah, for them, is not a relational being. That being said, the imam indicated that Islam believes that humanity is called to relationship — with God, but also to solidarity with other human beings.

He acknowledged Hebrew lawgivers and prophets as heroes of faith. He expressed a reverence for Mary, the mother of Jesus, and lauded Jesus as both prophet and rabbi. Islam rejects the idea that Jesus shared the divine nature while also having a human one. For them, God is too utterly transcendent to take on human flesh. On both doctrine and details we differ widely. Those familiar with the Old and New Testaments find that Mohammed’s version of Biblical stories often differs considerably from our own.

The imam emphasized the deep sense of ethics in the Koran. Theirs is a morality which respects women and children and sees men as called to protect them. He spoke of Islam’s concern for honesty and justice. He demonstrated his faith’s devotion to prayer and its great reverence for the holy. Indeed, he displayed quite a contemplative spirit in our sanctuary.

Finally, the point which the listeners found most memorable arrived. The imam commented on jihad, holy war. He insisted that scholars and Islam’s own “saints” understand holy war as something internal, something spiritual — the war waged within oneself. It is about conquering evil with good, vice with virtue. As he brought home that point, he became impassioned and declared that it was a perversion of his religion to turn jihad into propelling jets into buildings and killing thousands of people. He also said that the prophet (Mohammed) would not regard a person a martyr if he were to do such deeds. He lamented.

I’ve noted that in one of the most common English translations of the Koran, jihad is translated as conscientious “striving,” not holy war.

As terrorist onslaughts continue, I have to note that the Koran is so otherworldly that it is hard to fathom how it can be translated into the bloodthirstiness we keep seeing. Islam, if it is by the book, is more interested in what one might expect in heaven than what is transpiring in the politics of earth. By the imam’s account, his religion is more about cultivating gardens and submissive hearts than we might ever dream.

Further Reading

“Islam: What Catholics Need to Know”, by Rev. Elias D, Mallon, Ph.D., published by the National Catholic Education Association.