The Spring 2019 issue of Duquesne University’s alumni magazine features an article about a visitor to DU’s Palumbo Center. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor was there for a discussion on public service this past December. After the scheduled Q&A, she spent an unexpectedly long time strolling among the audience entertaining unscripted comments and questions. She answered law students, undergrads, and children thoughtfully and respectfully, interjecting humor and personal anecdotes.

However we may want to challenge Sotomayor’s judicial opinions (and Catholics will mightily want to do that on a number of them), we have to admire the fact that she had kept her commitment and even gone the extra mile while suffering from acute sciatica. The article briefly mentioned her impoverished childhood in a Bronx Puerto Rican ghetto but did not allude to the early death of her father or the Type 1 diabetes she has had since age 7.

In the latter decades of the last century, a number of book-length studies came out with titles like “Creative Suffering,” “Broken and Whole,” and “Creative Malady.” What these works revealed was a common theme in the lives of a surprising number of successful political figures, religious leaders, inventors, humanitarians, explorers, artists and medical scientists: their long hidden struggles. An unexpected number had grown up in poverty or endured the effects of disabling accidents or chronic illness.

Authors began to theorize about what they termed the “narcotizing effects” of concentration. The idea is that being consumed in a great quest is an effective pain reliever. Directing one’s attention to projects and persons changes our human perception of pain. While we are most lost in creative pursuits and good deeds, they found, we become unselfconscious.

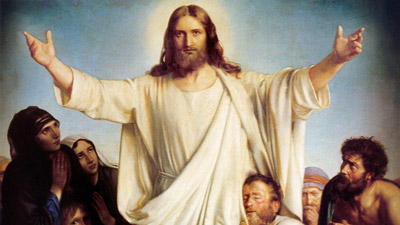

Christians have understood this for a long time. The adage to “offer it up” isn’t just about gritting our teeth and carrying on. It counsels us to direct our energies to the outer and the other — to God and the common good. If we are living this way, we are self-forgetful. We don’t have time to be taken up with our aches and pains.

That doesn’t mean that we carelessly neglect our health, but it does mean that we aren’t preoccupied with what we lack. If we are looking up and out, we will find what every good mother has always known: that caring for the needs of others shifts our attention to them. It keeps us from giving what some elders in my religious community have called an “organ recital” — telling anyone and everyone about our latest ailments, cholesterol levels, A1C’s, etc. Followers of Christ know what psychologists and neurologists have recently been figuring out: that when we offer up and offer out, we become more than we are and live more robustly.

St. Paul, who lamented the mysterious thorn in his flesh, noted, “I can do all things in Him who strengthens me.” He had learned to focus beyond his bones and skin. As we go through lifelong Holy Weeks, we can set our sights on the horizon and be Easter light to any and all.

Sister Pamela Smith, SSCM, is the Secretary for Education and Faith Formation at the Diocese of Charleston. Email her at psmith@charlestondiocese.org.