Hurricane Florence caused trees to fall on homes, business places to be ruined beyond repair, and floods to inundate parks, residential neighborhoods, and whole towns. Meanwhile, people in places other than North and South Carolina dealt with malnutrition, disease, gas explosions, and wild fires. In coming months, northern climates will deal with blizzards. Some frozen ponds will crack, and someone will fall through and drown.

It happens every day of every year. There are natural disasters which beset us. Heart attacks, cancer, and a host of illnesses and accidents strike children and adults. Miscarriages happen, and infants are stillborn. Every time the same questions arise. Why? Why us and not someone else? Why someone else and not us? And where is God in all this?

There is a term for the attempt to solve the riddle of innocent suffering. It is called theodicy, the attempt to reconcile our belief in a good God with what seems to be pointless, irrational evil. How do we wrap our minds around a God who is all powerful and all-merciful while witnessing chaos?

The problem with theodicy, the attempt to reason through the problem of evil, is that it offers some helpful insights but never arrives at final explanations. We just are not satisfied when we are told that some good may come of it — even though that is exactly what Christian faith proposes. From the time of St. Paul on, we have heard (as he wrote in his Letter to the Romans) that all things work together for good for those who love God.

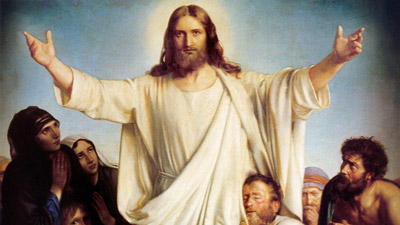

Similarly, we are not appeased when we are told that God knows all and foresees all but doesn’t stop everything that we perceive as damaging or dreadful. We know that God’s only Son died a hideous death and that there was more to the story: Easter. But we still don’t know why people who have never harmed anyone should end up being victims of brutality that isn’t wrought by humans.

Our problem is Job’s problem. When he loses everything — home, children, barn, livestock, employees, health, and the respect of wife and friends — he demands that God explain why. What he gets, in the end, is a reminder that he, Job, did not make the world and that he cannot understand everything. He is humbled and then restored.

For us, perhaps the best way to deal with suffering is to remember two things. The first is that our experience of evil is attributed to the willfulness of the first human beings who walked the earth — and decided that they wanted to be gods. We call their fateful choice original sin, and it affects the whole planet. We live in a broken world, even though the Redemption has happened. The second is that freedom seems to be a principle of the created order. We can attribute some suffering (caused by war, crime, spitefulness, or carelessness, for example) to the perverse choices of humans’ free will. But perhaps we can also account for some of our hardships by considering the freedom of the world of nature. Viruses and bacteria are free to land somewhere, volcanoes are free to erupt, and storms are free to gather. St. Thomas Aquinas long ago observed that “chance,” as he called it, is a part of Divine Providence.

In other words, things happen in a world set spinning by the Creator. We are free to accept that fact of life with the shrug of Job. We are also free to offer it up, in the hope that we may help someone somewhere — in Christ-like leverage — through what we have experienced and given over to God.

Sister Pamela Smith, SSCM, is the Secretary for Education and Faith Formation at the Diocese of Charleston. Email her at psmith@catholic-doc.org.